You are here

Home ›Black Hawk’s Bluff: A Sentinel to History

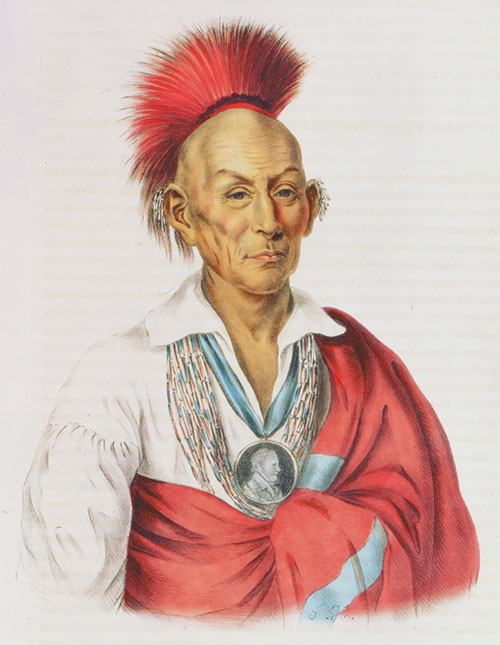

Chief Black Hawk ...

Historical landmark rises high above the New Albin area ... The prominent rock formation pictured above rises high above the scenic landscape in the Black Hawk Point Wildlife Management Area established by the Iowa Department of Natural Resources (DNR) two miles south of New Albin along State Highway 26 (Great River Road). The looming landmark has been identified as Black Hawk’s Bluff after Sauk Native American Chief Black Hawk, who is believed to have inhabited the nearby area. Submitted photo.

Editor’s Note: The following article was written and recently submitted for publication by northeast Iowa native Clyde Cremer. Cremer and his family moved to the New Albin area when he was in fourth grade, and he went on to graduate from New Albin High School in 1960, the last graduating class for that high school before it merged to form Kee High School in Lansing as part of the Eastern Allamakee Community School District. After his high school graduation, he enlisted in the U.S. Army before he completed a Bachelor of Science degree in Forestry from Stephen F. Austin State University and then a Master of Forestry degree from the Yale University School of Forestry and Environmental Studies, graduating from Yale with its Class of 1973 that also include Bill and Hillary Clinton and Dr. Ben Carson. He and his wife, Gail, first founded their American Log Homes business (now American Log Brokers) in 1977 in Missouri before moving its headquarters to Pueblo West, CO in 1984. Cremer has two grown children, Jeff and Kellie, and he and his wife, Gail, currently live in Pueblo, CO.

by Clyde Cremer

Black Hawk and the Cliff

When motorists traverse State Highway 26, barreling down this asphalt strip, listening to the radio, adjusting the air conditioner, and totally relaxed in the micro-environment of their vehicles, the last thing they are thinking about is the history that surrounds them. Yes, we are slaves to technology.

Nevertheless, the one prominent landmark that is hard to miss is that of the towering edifice above the Upper Iowa River, two miles south of New Albin. Once it was home to bears, turkeys (now reintroduced), passenger pigeons, elk, bison, wolves and peregrine falcons that used its crevices for nesting.

This landmark is locally known as Black Hawk’s Bluff, even though it is doubtful that Chief Black Hawk ever ascended its slopes to marvel at the panoramic landscape below.

The Bluff and Its Surrounding Environment

The bluff rises 940 feet above sea level and the cliff face itself is 80 feet high. The entire height of Black Hawk’s Bluff is 280 feet above the flood plain below. It is composed of Jordan sandstone which is the basis for other outcroppings in the area.

The cliff face was most likely exposed, after many thousands of years of erosion, by water from the ancient river (that is now the Upper Iowa River). The wind and rain also pummeled it due to the cliff’s constant exposure to these elements. The river was much higher in elevation in post-glacial times, but through the ages it cut a channel deeper into the underlying strata.

It is believed by geologists that, as the glaciers melted, the Mississippi River backed up into the Upper Iowa River and flooded areas that are high above the current river level. In fact, the various terraces or “benches” are alluvial deposits from this much higher ancient river’s flow. These alluvial deposits of sand and gravel were future sites for villages of the indigenous inhabitants in the area and, later, the settlers who misappropriated the Native American lands.

“The Cave”

One of the myths that surrounds the cliff is Black Hawk’s Cave. A few years ago, I was on an outing with a friend to the top of Black Hawk’s Cliff when a young man came puffing up the side of the bluff. He was looking for “the cave.” I soon filled him in on the geology of the area, which would make a cave out of sandstone more than unlikely.

Caves are found in limestone when water (somewhat acidic) dissolves the calcium carbonate and leaves sinkholes and caverns far underground, and in many cases are festooned with stalactites and stalagmites. The so-called cave of local lore is actually a rock shelter located at the base of the cliff. This rock shelter is 15 feet across its face, seven feet in depth and four feet in height. These rock shelters, whether large or small, gave cover and safety to the indigenous people in the era of semi-survival. There are a number of these rock shelters scattered through the rough hills of Allamakee County.

This rock shelter was excavated by several individuals in 1929. They were Ellison Orr, Dr. Warren Hayes, and Dr. Henry Field. Ellison Orr was an archeologist. The rock shelter had been inhabited for many years as a semi-permanent shelter from the elements and enemies. Without going into great detail, the excavation unearthed pottery shards, an arrowhead, charcoal, and bones of bears, deer, pigeons, fish, turtles, and turkeys. To say that life was tough for these people would be an understatement.

The Black Hawk War

During the Black Hawk War of 1832, the cliff sat as a silent witness to the bloodshed happening around it. It is quite probable that the U.S. soldiers who were trying to track down the last remnants of Black Hawk’s tribe used this elevated promontory to view the surrounding area for campfires, which would give away the location of this renegade band of Native Americans. It is inconceivable that Chief Black Hawk would have been hiding in “a cave” somewhere around the cliff.

The actual battle, if you could call it that, was carried out on an island near the mouth of Bad Axe Creek, across from New Albin. The remnants of the tribe were decimated shot, shell, and musketry, and they were at “the end of their tether!” Black Hawk actually gave himself up to the Winnebago tribe at Prairie La Crosse. He was then taken to Ft. Crawford where he was incarcerated. However, it is hard to dispel the local myth of Black Hawk’s Cave.

Sometime after the Black Hawk War, the Winnebago and the Sauk and Fox had a skirmish around the base of the cliff. Not much else is known about this conflict. The author of this paper found a spear point in this area in the mid-1950s, but a state archeologist stated that spears were not used after the native people obtained bow-and-arrow technology (about 1,500 years ago), so this spear point was not used in this skirmish.

The Early Inhabitants

The river now known as the Upper Iowa River was once located in what was called the Oneota Valley. This valley, and the surrounding area of Allamakee County, was believed to be inhabited by indigenous people for some 12,000 years. These early people were hunter-gatherers and used rock shelters for protection from the elements and predators, whether man or beast.

The PaleoIndian period was between 10,000 BC to 8,000 BC where they occupied the high hill tops along the river. The Archaic Period lasted from 8,000 BC to 1,000 BC, the Woodland period was between 1,000 BC to 1,300 AD, and the Oneota period was between 1,300 AD and 1,800 AD.

Between 1640 and the 1800s, the area was inhabited by the Mdewakanton Sioux, the Ioway (or in the Sioux language, Ayuhwa, which means the “sleepy ones”), the Winnebago, and the Sauk and Fox. The first whites to visit Iowa were Marquette and Joliet, who plied the Wisconsin River and then the Mississippi River to about 35 miles south of the Upper Iowa River. The next white explorers were Father Hennepin, Antoine Aquel, and Michel Accault, and it seems likely that they visited a village at the mouth of the Upper Iowa River.

Evidence still remains of the Native people’s occupation of this area. In fact, as a youngster, this writer found apiece of human skull (2-1/2 inches square) on a bluff west of Black Hawk’s Cliff. Now come the questions: Who? How? When? A fragment of a once-living human being whose life has been swallowed by the passing of time. In another bluff, across the river, in the 1960s, some hikers from New Albin found two skeletons in an obscure crevice. The skeletons were of a woman and a baby. At the time, archeologists felt that the baby and mother probably died during childbirth. Members of her tribe interred both of them in this natural sarcophagus.

A mile to the south of the cliff is a site known as Fish Farm Mounds State Preserve (named after the former owners, the Fish family). The ancient inhabitants, known as the Red Ochre People, built these mounds as they did many others in northeast Iowa. Some excavations of these mounds produced arrowheads, pottery shards, and some beads. In some areas, copper items were found which supports the belief that they traded all the way to the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, where placer copper can be found in a fairly pure form.

Plant Geography

An interesting phenomenon of this area is the growth of prairie plants (in lieu of trees) on the southern slopes of hills. This is due to the warmer and drier climate on these south facing slopes. These climatic anomalies are referred to by plant geographers as grassy balds. To dispel another myth(s), these grassy balds, devoid of trees, were not caused by Native Americans burning the hillsides or the railroads cutting the trees for railroad ties.

On the top of Black Hawk’s Cliff can be found plants such as Pasque flowers, the shooting star flower, and the compass plant. These are normally found only on the Great Plains. However, the climate is changing and the hills that this author used to hike are now so thick with brush that a raccoon could hardly get through the tangled mess. The precipitation has increased greatly in the Upper Midwest since the 1950s and the result is that many grassy balds have been taken over by cedar and hardwood trees.

Eastern Red Cedar can be found in precarious positions growing on the edge of exposed cliffs. The cedar trees grow slowly as they cling to life with minimum amounts of soil moisture and nutrients. These small, twisted trees are referred to as Krumholtz by plant geographers.

This writer studied the cross-sections of two of these trees. One of these depauperate trees was only three feet tall and had started its growth in the early 1800s. The other tree, about 12 feet tall, began life in about 1720! Both trees were dead at the time of sampling, so I had to ascertain the approximate date of death.

By the way, this author does not believe in destructive sampling, so only used dead trees for tree ring analysis also known as the science of dendrochronology. These trees showed the increase and decrease of competition near them, but the study did not lead to any remarkable insights into rainfall patterns.

The Town of New Albin

On one of the terraces discussed earlier, a former Native American village became the town of New Albin (formerly called State Line), which can be seen two miles to the north of the bluff. The residents of New Albin constantly find archaic artifacts from the former residents in their gardens and construction sites.

In 1915, a stone tablet was found during a basement excavation. A petroglyph was etched on a slab of Catlinite, or pipestone, which is only found in southwest Minnesota. The slab is etched with a petroglyph of a warrior and a horse. It had to have been purposely buried as it was several feet under the soil surface. It now resides in the visitor’s center at Effigy Mounds National Monument.

One of the historic novelties located on the northern edge of the town is “The Iron Post.” Before statehood, the territories of Iowa and Minnesota had a dispute as to where the boundary between them should be located. Minnesota believed that it should be at the Upper Iowa River. The dispute was settled by the U.S. Congress on August 4, 1846.

In 1849, Capt. Thomas J. Lee placed a cast iron obelisk at its present spot, the southern boundary of Minnesota. Quite frankly, as a resident of New Albin and the surrounding area, I am glad they made the Iowa-Minnesota border north of New Albin because I couldn’t take those Minnesota winters.

The Sand Cove

A geologic phenomenon can be found a mile to the west and is locally known as Sand Cove. The ancient river was once so much higher than its present location that the river deposited a deep layer of sand, in what was an ancient beach, that transcended a large area. The sand deposits were largely exposed so that a strong wind would deposit drifts of sand across the roadway.

This author’s family owned a farm in this area. The sand formed a dike where the trees along a fence line would catch the blowing sand and form a loess deposit. Today, good farming practices have stabilized this sand in the Sand Cove and little of the original expanse of sand can be seen.

Recently, fracking companies wanted to mine this sand for their oil drilling operations, but the local landowners said no. A pioneer cemetery is located in the Sand Cove on the former property of Peter Colsch and family.

Zebulon Pike and Chief Wapasha

In 1805, explorer Zebulon Pike (yes, of Pike’s Peak fame) left St. Louis to find the source of the Mississippi River. On a rainy day, September 10, 1805, Pike paid a visit to the village of the Mdewakanton Sioux Chief Wapasha. This village was located on the south side of the Upper Iowa River, near the mouth, at a small bend in the river that can be seen from the top of Black Hawk’s Cliff. The village had been located at this site since around 1800.

The soldiers had shot at some pigeons earlier (probably passenger pigeons) and thus Chief Wapasha was forewarned of their friendly arrival. Zebulon Pike had met the Chief days earlier in Prairie du Chien, WI and called him La Feuille, meaning “The Leaf” in French. The expedition was greeted with three rounds of friendly musketry, which Pike answered in kind. However, the warriors in the village were on a ration of whiskey and their aim was not very accurate. Thus, Zebulon Pike was worried about his men’s safety.

When he went ashore, he had his pistol in his belt and his sword in his hand. He was then invited into the Chief’s lodge. After the fanfare, the expedition and the villagers had food and refreshments (probably more whiskey). When Zebulon Pike departed, the Chief gave Pike a peace pipe and he gave the Chief more whiskey. This was the medium of trade between the whites and the Native Americans. When the meeting ended, Zebulon Pike headed north to Prairie La Crosse (present-day La Crosse, WI).

There has been some recent thought about an excavation of this village site along the Upper Iowa River, but after 200 years of flooding, siltation, and the dredging of sediment from the river, starting in the mid-l950s, it would probably be an exercise in futility.

Note: A good read is the “Diary of Zebulon Pike”, available in larger, well-stocked libraries.

Gabbitt’s Cabin

A photo from around 1870-1880 shows that all the trees had been clear-cut to build a corral and later a cabin, which was constructed of square, hewn oak timbers. It was not very large, but the occupants were lucky to have even this modest home. This was also called the Brookman’s cabin, which probably preceded Gabbitt’s cabin. In the mid-1950s, the landowners removed the dilapidated structure and hauled off the timbers for some unknown use.

Occupation Below the Cliff

As a youngster, this author’s family lived under the shadow of the cliff in the frame home built in the late 1920s or early 1930s. When the basement was excavated, the contractors found pottery shards, arrowheads, and some bones. The basement had an unpaved floor and I found a complete arrowhead there, as well as one lying on the unpaved garage floor.

The Native Americans who lived there prior to the frame dwelling had a good spot for an encampment. It was near the river, its forest provided firewood and building materials, and it had game for food. Where the artesian well now stands, in an earlier time there may have been a spring.

Local historians from New Albin claim that a fort was located where the Iowa River Road and Highway 26 now meet. I expect that this was on the terrace overlooking Hays Lake. This fort was constructed at the time of the Black Hawk War and after it was abandoned, the local natives moved in and used it for whatever purpose they could. One of these natives was Chief Decorah and family and the Thompson family. I expect that this was not the Chief after which the town of Decorah, in Winneshiek County, was named. I have found references to a number of Chiefs by the name of Decorah in my readings.

The Area Today

So, what has happened to these historic sites where the ebb and flow of human civilization eked out a living for thousands of years? The alluvial terraces were plowed into farm fields and the flatlands along the river flood plain and the silver maple, cottonwood, and willow trees were dozed into piles and burned prior to cultivation.

As an example, I hunted for arrowheads on the terrace above Hays Lake some years ago. Yes, I found a small, intact arrowhead that was dropped unnoticed by its maker. A short time later I found a Liberty Head five-cent piece from 1917. On the first find I could envision the encampment of indigenous people from an unknown era, and on the second I could see a farmer with his horse-drawn, single bottom plow cutting another furrow. He then stopped to wipe his brow on a hot summer day, pulling out his handkerchief, as well as five-cent piece that he accidentally dropped on the ground.

Civilizations come and go, but they leave some of their cultural items behind for future generations to ponder. If these remnants could only talk - just like the silent sentinel that has overlooked the Oneota Valley for eons: Black Hawk’s Bluff.

Sources:

• Knudson, Dr. George. Guide to the Upper Iowa River. Luther College. Decorah, IA. 1970.

• Orsi, Jared. Citizen Explorer: The Life of Zebulon Pike. Colorado State University.

• Orr, Ellison. The Rock Shelters of Allamakee County, Iowa. A Preliminary Study. Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science. Vol. 38-Article 41. Iowa City, IA. l931.

• Orr, Hayes and Field. The “Black Hawk Cave” Rock Shelter. Survey and Excavation. Unpublished. 1930.

• Sires, Iris. The First 100 Years of New Albin. Locally Published. 1995.

• Vogel, Robert C. Allamakee County, Iowa. Historic Archeology Overview. BCA No. 6. The Allamakee Historic Preservation Comm. Allamakee, Iowa. May 1989.